Be a good Kubernetes citizen and use Pod Disruption Budgets

KubernetesOperationsDevOpsTerraform

The appeal behind using Kubernetes is that you abstract the details of where your applications run and leave it in k8s’s hands. It’ll schedule containers following some given constraints, and restart them if they crash.

However, a Kubernetes cluster is not a perfect abstraction. That is especially visible as an operator. Even if you use a managed solution like AWS EKS, you still have to perform some maintenance yourself.

As an operator, I want this maintenance to happen regularly, to avoid stagnation and prevent failure. As a developer, I avoid unwanted interruptions for my applications. A Pod Disruption Budget (PDB) is a resource in Kubernetes that harmonizes both needs. I want to talk about how to use it in this article.

Pod Disruption Budgets to the rescue

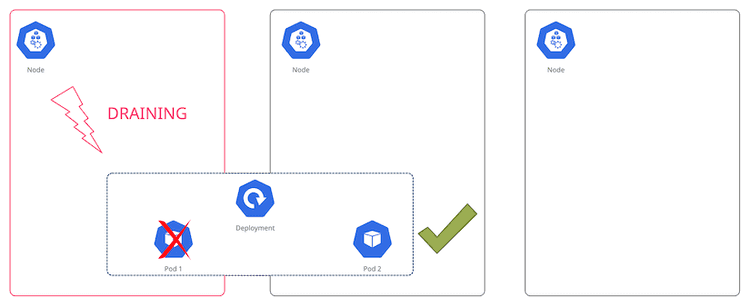

A classical maintenance scenario in the world of Kubernetes is the replacement of a worker node. There are many reasons: A version upgrade, a new AMI being rolled out, or an adjustment in the instance size. When the old node is replaced, the Pods running there will get evicted and rescheduled. In k8s parlance, this is called a voluntary disruption. If your application gets an unplanned, unwanted downtime you’ll think of it as pretty damn involuntary. Swearing might happen.

Luckily, somebody has thought of this. With a PDB you define how many Pods have to remain available at all times in a Deployment (or similar). If you replace worker nodes one by one, the scheduler ensures that the application still runs some Pods in the remaining nodes throughout the process, avoiding the dreaded downtime.

The cool part is that it’s enough to define it as an extra resource and apply it as part of your application release. It’s decoupled from any operational action, which makes it very convenient to use. Here is the official documentation.

Do you actually need to use PDBs?

This is a fair question. PDBs should be reserved for applications that need to remain online.

If your application can allow some minor downtime, it might be easier to let it happen instead of putting an unfair burden on the operators of your cluster.

As we’ll see in a bit, if you misconfigure a PDB nodes can’t be drained, making these nameless operators mad at you. Nobody wants to be the blocker. Let’s not do that.

Creating a PDB

Alright, so let’s get down to basics and create one such PDB. Usually, you’ll have one Deployment that you want to protect from downtimes.

A simple deployment

Let’s show some Terraform code.

locals {

app = "hello-world"

image = "nginx:1.14.2"

port = 80

}

resource "kubernetes_namespace" "this" {

metadata {

name = "${local.app}-namespace"

}

}

resource "kubernetes_deployment" "this" {

metadata {

name = "${local.app}-deployment"

namespace = kubernetes_namespace.this.metadata.0.name

labels = {

app = local.app

}

}

spec {

replicas = 2

selector {

match_labels = {

app = local.app

}

}

template {

metadata {

labels = {

app = local.app

}

}

spec {

container {

name = local.app

image = local.image

port {

container_port = local.port

}

}

}

}

}

}This is a simplified deployment of an NGINX image. We are running two replicas to ensure availability. Now, let’s create a PDB for this deployment.

The PDB

The PDB is another resource in Kubernetes. As of the date of this post, its apiVersion is still policy/v1beta1.

You need a target. It uses the same selector as the deployment, which we reuse. The Pods created by our previous Deployment are subject to this PDB.

The crucial part of this resource is specifying how many Pods you want to keep up at all times. You have to provide one of maxUnavailable or minAvailable, but not both. They do what you’d expect. In my example, I want to ensure that there is always at least one instance running.

resource "kubernetes_pod_disruption_budget" "this" {

metadata {

name = local.app

namespace = kubernetes_namespace.this.metadata.0.name

labels = kubernetes_deployment.this.metadata.0.labels

}

spec {

min_available = "1"

selector {

match_labels = kubernetes_deployment.this.spec.0.selector.0.match_labels

}

}

}And that’s it. Once I’ve applied this resource, Kubernetes respects the constraint when draining a node. Now we can replace these nodes knowing that my application won’t experience downtime in the process. I mean, as long as we don’t destroy all nodes at once, you know.

Don’t block maintenance!

When you are using PDBs, you have to be mindful of not creating impossible scenarios. For instance, if you have a Deployment with only one replica, setting minAvailable = 1 will ensure that the Pod is never voluntarily evicted.

This is bad! Node maintenance is necessary. Your Pods should be flexible coming in and out of the system. Besides, a PDB doesn’t prevent involuntary evictions. If the EC2 hosting a node goes down, you’re screwed. Don’t do this.

Summary

By adding a Pod Disruption Budget resource we make sure that our application remains online during maintenance windows. It saves a lot of coordination effort between people operating the system, and people running applications that should remain online.